Comerica, Conduent, and the U.S. Treasury Betrayed Veterans and Other Victims

The Kindle version is available at Amazon. The print version is in production an will be available soon at Amazon, at our website, and other outlets.

Below is the article published May 29, 2023 regarding my book and the corruption at Treasury and Comerica Bank.

Comerica in ‘serious violation’ of Treasury’s Direct Express programBy Kate BerryMay 29, 2023, 9:00 p.m.  Internal communications obtained by American Banker indicate that bank officials were concerned about the legality of the bank’s third-party vendor relationships retained as part of its contract with the Treasury Department to operate Direct Express, a public benefits payment system.Bloomberg News

Internal communications obtained by American Banker indicate that bank officials were concerned about the legality of the bank’s third-party vendor relationships retained as part of its contract with the Treasury Department to operate Direct Express, a public benefits payment system.Bloomberg News

Comerica Bank officials privately acknowledged significant compliance failures in their operation of a Treasury Department program that provides federal benefits on prepaid cards to millions of unbanked Americans, according to internal documents obtained by American Banker.

A Comerica executive said the Dallas bank faced a “serious contract violation” for allowing fraud disputes and data on Direct Express cardholders to be handled out of a vendor’s office in Lahore, Pakistan, the documents show.

Personally identifiable information on veterans, Social Security and disability recipients were routinely shared and handled by i2c Inc., a vendor based in Redwood City, Calif., with an office in Lahore, Pakistan — in violation of the government contract, the Comerica executive said. The Treasury’s agreement with the bank states that all services provided “shall be performed in the United States or its territories.”

Paul Lawrence, who served as under secretary for benefits in the Department of Veterans Affairs from 2018 to 2021, said he was in “complete shock and disgust” after being told of the information contained in the internal Comerica documents.

“All of these government contracts basically say you have to be in the U.S. and the program has to be run by U.S. citizens,” Lawrence, a longtime government consultant, said in an interview. “This has all the makings for a really, really bad situation.”

The internal documents, in addition to court documents filed in a class action last year, paint a broader picture of the $91.2 billion-asset Comerica’s strategy and third-party oversight of Treasury’s Direct Express program, which serves 4.5 million Americans.

Comerica has been mired in litigation and yearslong disputes over Direct Express, which it has operated under a contract with the Treasury since 2008. Direct Express deposits roughly $3 billion a month electronically on prepaid cards to millions of federal government beneficiaries who do not have a bank account. The program is part of a government effort to reduce potential fraud and costs by weaning people off paper checks.

Comerica has contracted out the day-to-day operations of Direct Express to two vendors: i2c and Conduent Inc., a publicly-traded conglomerate based in Florham Park, N.J.

The internal documents include a 2020 email from a Comerica executive, who described sweeping violations of Regulation E, which governs how a financial institution addresses errors reported by consumers including for theft or fraud. Nora Arpin, Comerica’s then-senior vice president and director of government electronic solutions, said the bank was in breach of its Treasury contract but that it was unable to get its third-party vendor to make changes.

“Management for Reg E dispute processing is in Lahore which means that cardholder information is being shared with/sent to Lahore, which is a serious contract violation,” Arpin wrote.

Arpin no longer works at Comerica. Arpin and an attorney who had represented her in the past did not respond to requests for comment.

David P. Weber, a clinical assistant professor of accounting at Salisbury University and a former supervisory counsel and enforcement chief at the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., said the bank would need to inform its regulator about the activities of third-party service providers.

“It was a clear violation of the contract Comerica held with the Department of the Treasury to locate the vendor in a foreign country when part of the consideration for them being awarded this federal contract was to use American employees and vendors,” said Weber, who served as special counsel for enforcement for more than 10 years at the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency.

“Separate and aside from contract fraud, it is inappropriate for a federally-insured depository institution to locate third-party service provider activities in a foreign nation without informing their regulator, and locating the operations in a country in which there are questions about rule of law, which would make supervisory and exam activities as well as protections of American consumers questionable.”

The bank previously had been criticized by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas in a “matters requiring attention” order a year earlier, which described “weaknesses” in Comerica’s risk monitoring of Direct Express, according to court documents. Examiners said Conduent, the bank’s primary vendor, did not provide cardholders reporting fraud on their cards with information on how to receive a provisional credit, documents show.

CARD FRAUDComerica scrambles to address fraud in prepaid benefits programAugust 26, 2018 1:51 PM

Comerica was paid $151 million in 2020 to operate Direct Express, and received roughly $770 million in total gross revenue over a six-year period, from 2015 to 2020, to run the program, Albert Taylor, a Comerica senior vice president and director of National Bankcard Services, said in court documents.

In response to questions from American Banker, a Comerica spokeswoman said the bank is “proud to have served as financial agent for the Treasury Department’s Direct Express Program since its inception in 2008.”

“Should an issue arise with a third-party vendor involving compliance with the Financial Agency Agreement, Comerica works closely with the vendor to address the situation, in accordance with Comerica’s obligation under the FAA to ensure its vendors’ compliance with the FAA,” the Comerica spokeswoman said in an email. “Additionally, Comerica promptly notifies [Treasury’s Bureau of] Fiscal Service of issues impacting the program and keeps Fiscal Service apprised until they are fully resolved.”

Conduent declined to comment. Executives at i2c declined an interview but instead provided a written statement disputing allegations it had violated its contract.

“As a global provider of banking and payment services, we naturally employ a global workforce. One that spans more than six countries — a fact that we are proud of and that our partners are actively made aware of and accept,” i2c said.

“Let it also be known that i2c’s compliance regarding the access, use, storage, and transmission of cardholder information is independently certified by third parties including, but not limited to an annual [Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard] certification, which requires the encryption or masking of personal identifiable information regardless of geographic location,” reads the statement.

The Treasury’s Bureau of Fiscal Service did not return calls seeking comment. The Treasury’s Office of Inspector General said it had no comment.

Inadequate fraud reporting

In a key internal 2020 email, Arpin, the former Comerica executive, listed 13 bullet points describing the practices of i2c. Among the bank’s “serious concerns,” she wrote:

● “We are having significant difficulty getting adequate fraud reporting.”

● “We can’t get the Call Center statistics we need.”

● “Reg E adjudication is an issue”

● “Fraud prevention is a serious issue.”

● “Reporting in general is an issue — we aren’t getting the reporting that the [Treasury’s Bureau of] Fiscal Services requires.”

Arpin also wrote in the internal email that i2c’s CEO Amir Wain “doesn’t have plans to fix those issues.”

Cardholders have complained for years about fraud, poor customer service and high fees in the Direct Express program.

Last year, a federal judge certified a class action against Comerica and Conduent brought by Direct Express cardholders who claimed their accounts were drained of thousands of dollars from 2015 to 2022 due to fraud. The class action, filed in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas, alleges that Comerica and Conduent denied refunds to cardholders who alleged fraud on their accounts.

The court documents, combined with internal documents that American Banker received anonymously in the mail, provide a better understanding of Comerica’s private and public responses to various inquiries.

Comerica executives were repeatedly warned about vendor oversight, potential breaches of the Treasury contract and deficiencies in the bank’s compliance management system, said sources familiar with the matter who asked that they remain anonymous out of fear of retaliation. In-house lawyers escalated their concerns to the bank’s senior leadership, including Susan Joseph, Comerica’s head of compliance; Jay Oberg, senior executive vice president and chief risk officer; and Peter L. Sefzik, senior executive vice president and chief banking officer.

The Treasury’s Office of Inspector General issued reports in 2014, 2017 and 2020 that were critical of compliance, chargeback and dispute processing at Direct Express, which Comerica manages, in addition to the bidding process for the government contract. The OIG investigates waste, fraud and abuse in the agency and programs it oversees.

In August 2018, Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., launched an investigation into Direct Express after cardholders complained about not being reimbursed for fraud. In a letter to the Veterans Administration, Warren said fraudsters had used “stolen data to impersonate benefit recipients, made fraudulent purchases, and drained the prepaid cards of the federal benefits.”

CARD FRAUDWarren rebukes Comerica over fraud in benefits programOctober 16, 2018 5:30 AM

Comerica’s Executive Chairman Ralph W. Babb responded to Warren by stating that Comerica has taken appropriate steps to root out fraud.

Comerica “follows all laws and regulations including the [Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council] guidelines for supplier oversight,” Babb said in a 21-page response in October 2018.

‘Reg E Lite’

Yet, within a month of Sen. Warren’s inquiry, a Comerica lawyer tried to convince a Texas bank examiner that Regulation E does not apply to the bank or to federal government beneficiaries, the internal documents show.

The Comerica lawyer was responding to a query from the Texas Department of Banking by claiming that the bank was not fully required to abide by the Electronic Fund Transfer Act, which is implemented by Regulation E. The regulation sets strict timelines for banks to resolve errors including investigating fraud and reimbursing harmed consumers with provisional credit when money is stolen.

“Program customers only get ‘Regulation E Lite,’ benefits,” a Comerica executive in the bank’s legal department wrote in 2018. That lawyer described “why [the] program’s customers are not entitled to all of the provisions and benefits of Regulation E.”

In the email, the Comerica lawyer wrote that “…neither the Federal Electronic Funds Transfer nor its Regulation E applies to the Comerica Bank under the Program as a ‘financial institution.”

Comerica argued that the Treasury, not the bank, was considered to be the financial institution for Direct Express, “which is why we generally state that Program customers are only entitled to ‘Regulation E lite’ benefits.”

By August 2019, Joseph, the chief risk officer, had forwarded the email about ‘Reg E Lite,” to another Comerica lawyer.

Comerica submitted a glossy, 67-page application to the Treasury in early 2019 in which it described the vendor, i2c, “as a leader in transaction processing, security, fraud prevention and innovation.”

In 2020, Treasury renewed Comerica’s contract after i2c was hired to handle new cardholders. The agreement with the Treasury was signed by Babb, who retired in 2019. Babb was succeeded by Curt C. Farmer, Comerica’s chairman and CEO.

Experts say banks have a general obligation to act in good faith when dealing with customers.

Weber, the accounting professor and former regulator, said the bank’s legal and compliance obligations far exceed Regulation E. He also called into question Comerica’s third-party risk management and operational risk standards.

“The unbanked people already are more vulnerable than ordinary bank customers because they don’t have the skill set or financial acumen to know what their rights are, and it’s compounded when they are victims of fraud,” Weber said. “At the end of the day, federally insured depository institutions are required to have appropriate third-party risk management processes in place, and it isn’t new to prepaid cards or benefits.”

Weber noted that Bank of America was hit with a $225 million consent order last year for failing to investigate fraud claims in unemployment benefits.

“The idea in a perfect world is that somehow the third-party vendor can do it faster and cheaper than the bank because they think they’re not obligated to follow the same rules,” said Weber, who analyzes counterproductive work behavior. “It’s an operational risk issue if the third-party doesn’t have the policies, procedures and controls to identify systemic issues.”

VA finds a way out

The myriad problems in the Direct Express program, which Comerica manages, forced the Veterans Administration to devote resources to helping veterans find an alternative. By 2019, the VA helped create the Veterans Benefit Banking Program, a consortium of banks and credit unions that offer free checking accounts so veterans can receive their monthly payments via direct deposit.

“We made a super-conscientious effort to get veterans off Direct Express because the bad experiences were just gut-wrenching,” said Lawrence, the VA’s under secretary for benefits.

Steve Lepper, a retired U.S. Air Force Major General who is president and CEO of the Association of Military Banks of America, a trade group, worked with the VA to create the program.

“The complaints the VA was getting finally pushed them to the point where we needed to create an alternative to the Direct Express program,” Lepper said. “Veterans were apoplectic about all of the problems that they were experiencing with the Direct Express program and, of course, Comerica was responsible for all of the management of the program — including the fraud investigation and resolution processes.”

Roughly 240,000 veterans have migrated away from Direct Express and now have bank accounts with direct deposit, Lepper said. About 80,000 unbanked or underbanked veterans still receive their benefits on Direct Express prepaid cards or paper checks.

Lepper credited J.B. Simms, an author and private investigator in Brighton, Tenn., who recently published a book titled, “Comerica, Conduent and the U.S. Treasury Betrayed Veterans and Other Victims.” Simms says he first discovered fraudulent charges on his Direct Express account in January 2017 and a second time later that year. He then sought to help other veterans recover money that was stolen due to fraud, including those in which veterans’ claims were denied.

Alleged violations

Simms and others say Comerica’s failure to address problems with Direct Express should get a public airing.

“The Direct Express cardholders are the most vulnerable population of all Social Security recipients, and most do not have bank accounts and lack the sophistication to challenge any authority,” said Simms. He is one of just eight named plaintiffs in the case.

Another plaintiff, Harold McPhail, a Vietnam veteran, reported that $30,000 was stolen from his Direct Express account in 2018. But he died before getting a resolution, said his daughter Martisha McPhail, who said Conduent initially denied her father’s fraud claim.

Some Social Security recipients who reported fraud have lost hope that they will ever be reimbursed for thousands of dollars they say was stolen off their prepaid cards. Some said they have not been notified of the class action or any efforts by the bank to reimburse them.

Mike Colburn, a retired Las Vegas businessman, alleged that $5,500 was stolen from his Direct Express account in 2018. Colburn said he was unable to make his mortgage payment and had to borrow money from relatives to avoid defaulting. He ultimately was reimbursed $500 by Conduent but was never able to get all of his money back.

“I gave up on talking to that bank,” Coburn said. “They don’t return phone calls, they don’t return emails and Conduent accused me of stealing the money from myself.”

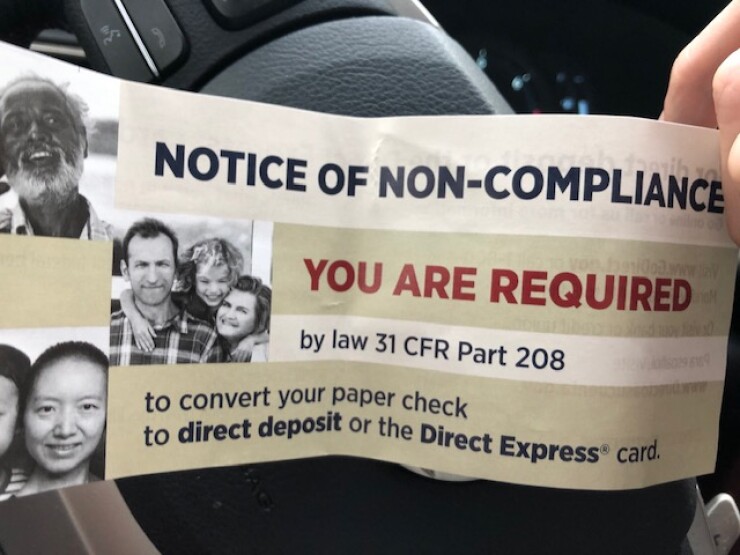

After money was allegedly stolen from his Direct Express account, Colburn called the Social Security Administration to sign up for paper checks. Now his monthly Social Security check comes with an insert stating that he is breaking the law for not using Direct Express, he said.

Cardholders allege in the class action that they were not given provisional credit when errors were reported and were not sent the results of investigations in a timely manner. Regulation E requires that a financial institution investigate fraud within 10 days of being notified by a cardholder, but the bank can take up to 45 days to investigate if they provide provisional credit in the amount of the alleged error.

“Nobody could get through to the call center and most of the time people never filed a claim because they got locked out of their accounts,” said Jackie Densmore, a plaintiff in the class action, who is a caregiver for her brother-in-law, Derek Densmore, a disabled Marine. She alleged $800 was stolen from his Direct Express card in 2018 and described hours spent trying to get through to Conduent on the phone and being told to submit a claim in writing.

“There are all these people out there who were never able to complete a fraud packet and actually file a claim,” Densmore said.

The vendor had run into problems before with government oversight. Conduent was fined by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau in 2019 for unfair student loan practices, and in 2017 for sending incorrect information to credit reporting agencies. In 2019, Conduent, which at the time was owned by Xerox Corp., agreed to a $235 million settlement with the Texas attorney general for Medicaid-related claims.

Densmore also switched to paper checks for her brother-in-law, who has post-traumatic stress disorder. Symptoms resurface every month, she said, when he sees the insert from Social Security that states: “Notice of noncompliance. You are required by law to convert your paper check to direct deposit or the Direct Express card.”

“Every month we relive the nightmare from five years ago,” she said. “Since Derek has a medical condition, I have to explain to him every month about the situation that we have gone through with Direct Express and that he is allowed to get a paper check.”

What’s next for Comerica customers?

Court documents show that in May 2019 alone, Comerica received 15,712 fraud disputes, according to Taylor, Comerica’s director of National Bankcard Services. Taylor said in court documents that Comerica did not have any data to identify cardholders that reported fraud, and the bank didn’t keep track of money refunded or denied for fraud.

The supervisory letter from the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas in early 2019 identified potential consumer harm, program deficiencies and customer service issues in Comerica’s handling of Direct Express. Specifically, examiners at the Dallas Fed said that Conduent’s call centers were not trained in Regulation E and did not tell cardholders who reported fraud that they could receive provisional credit as part of the process of filing a dispute.

“Only those callers who specifically asked for instructions or inquired about the provisional credit process received any guidance,” the Dallas Fed stated in the supervisory letter sent to Joseph, Comerica’s head of corporate compliance.

In addition, Conduent required that cardholders provide documents and a written statement but did not state that cardholders had 10 days to do so or they may not receive provisional credit.

“While [an] explanation of provisional credit is not a regulatory requirement, the recurring consumer complaints regarding provisional credit indicate consumers are adversely affected,” the Dallas Fed stated.

It also noted more systemic problems in the collection of data.

“There is no root cause analysis of complaints to identify systemic issues and trends that warrant immediate correction,” according to the supervisory letter. “Comerica must establish a method of identifying root causes of complaints originating at Conduent and track complaints with serious allegations or high compliance risk, such as [unfair, deceptive acts and practices.]”

A problem of incentives

In its bid for the Treasury contract, Comerica said it is “committed to delivering a low-cost solution, while providing ready access to funds and protecting both the Direct Express cardholder and the overall program.”

Comerica receives fees, interchange revenue and annual payments from the Treasury that rose to $151 million in 2020, the most recent data available, according to court documents. Of that total, Conduent received $105 million in 2020 from Comerica, Mitch Raymond, a senior director in account management at Conduent, said in court documents.

Comerica also benefits from an estimated $3 billion a month in low-cost, non-interest-bearing deposits from the Direct Express program, sources familiar with the program said. The deposits boost the bank’s liquidity at little cost and can be leveraged, allowing the bank to lend to more customers, sources said.

Last year, Comerica disclosed that the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is investigating some of its business practices. The Texas bank stated in a regulatory filing in February 2022: “Remedies in these proceedings or settlements may include fines, penalties, restitution or alterations in the corporation’s business practices and may result in increased operating expenses or decreased revenues.”

Weber, the former FDIC enforcement chief, said that regulators typically take into account whether information exists to indicate that a bank “is willfully in noncompliance with the law.” To deter misconduct, regulators may factor into a civil money penalty whether a bank’s executives and board directors believed a potential fine would be lower than the cost of compliance.

“It’s a mixture of misplaced financial incentives combined with failing to have appropriate board and management oversight over different operational areas of the bank,” said Weber, who also served as a former assistant inspector general for investigations at the Securities and Exchange Commission. “When evidence indicates that individual officers or directors have made decisions to allow misconduct and violations of the law to occur, it is well past time to not only hold the bank accountable but to hold the individual officers and directors and the entire board personally accountable.”

Simms, one of the plaintiffs in the class action, lays the blame for the problems on shoddy third-party oversight by the Treasury.

“The Bureau of Fiscal Service, as a part of the U.S. Treasury, allowed Comerica Bank to continue violating federal banking laws and endorsed the contract with Comerica knowing inaccurate information was submitted by Comerica to obtain the contract,” Simms said, citing the OIG reports.

Lepper, who helped create the alternative option for veterans, said he didn’t understand why the most vulnerable citizens were not getting the attention of Comerica top executives.

“Why didn’t they make the obvious improvements to their program to avoid all of this?” Lepper said.